Chasing the Lowrider Muse

BY KATHERINE WARE

It takes a special vision and a lot of hard work to transform an abandoned car into a one-of-a-kind sculpture on wheels, but that’s exactly what makes New Mexico’s lowriders so extraordinary.

Ordinary life screeches to a standstill—or at least a creep—when the lowrider arrives with its over-the-top style, declaring its owner’s pride in his or her creativity, heritage, hometown, family, and faith. Not surprisingly, lowriders have captured the imaginations of people all over the world, as the New York Times recently affirmed in the article “Lowriding Culture Goes Global” (December 6, 2015).

Lowriders appeal to all the senses, offering music for the ears and plush upholstery for the fingertips. And perhaps most of all, they provide a visual feast with gleaming chrome, sparkling paint, meticulous pin-striping, and artful murals. So it’s no surprise that artists gravitate to lowriders. Just as northern New Mexico’s stunning landscape and varied cultures have inspired visual artists over the centuries, so, too, has the region’s distinctive tradition of lowriders been an inspiration for painters, photographers, sculptors, and others. Con Cariño: Artists Inspired by Lowriders acknowledges the lowrider as a prominent cultural icon and offers a small sampling of work created by the many artists who celebrate these slow-moving palaces.

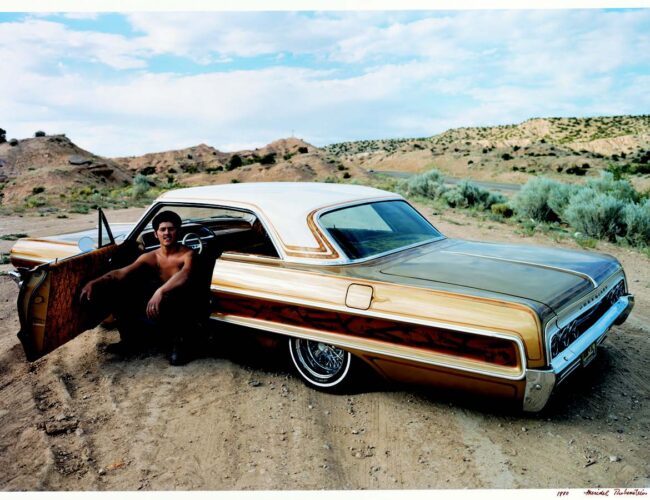

Artist Meridel Rubenstein got involved with lowriders by accident in 1979 after completing a series of photographs on the craftspeople of New Mexico for a show at the Albuquerque Museum. Collector Ray Graham chastised her for leaving lowriders off that list and encouraged her to photograph them.

“I wasn’t interested in cars,” Rubenstein said, but she was interested in art and people and culture, and her work with lowriders opened up a new world for her. “It changed my life,” she said. “Their use of velvet and chrome together was a powerful combination.…It was from that point on that I began to work with disparate materials.” Rubenstein’s photographs were the subject of the museum’s 1980 show The Lowriders, displayed outdoors on the Santa Fe Plaza alongside lowrider cars.

While Rubenstein came to lowriders as an outsider to the culture, other artists are insiders commenting on the northern New Mexico and Hispano traditions they absorbed growing up here. Contemporary santero Luis Tapia has created numerous works of art about lowriders, carving dashboards, processions, and small vehicles that evoke the color and pageantry of the lowrider experience. Tapia also tried his hand working with the real deal, a Cadillac that he patched, painted, and sawed in half before customizing it with his brush. A slideshow by Santa Fe photographer Jack Parsons charts the creation of this piece, titled A Slice of American Pie. The car itself is now in the collection of the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque.

Another local santero, Arthur López, has returned to the subject of the lowrider many times in his art-making, often with a humorous sensibility: “I believe that car culture and santos go hand in hand. Growing up in a Hispanic Catholic family in New Mexico, all of our new vehicles would be blessed and a saint added to the dashboard as a form of protection on our travels. I pay homage to these memories by incorporating these traditions in my art.”

Using traditional materials and techniques, López creates sculptures that bring to light the close connection between religion, community, and car culture in work such as Sangre de Cristo Cruzin with the Lowered, in which a red lowrider truck prepares to travel into the embrace of the northern New Mexico landscape under the watchful gaze of Jesus. López is also a collector of work by other artists inspired by lowriders, and has generously loaned some of his pieces to the museum for this exhibition.

Photographer Alex Harris’s views of the interiors of lowriders—often equally elaborate as the exteriors—were made in the late 1970s, when he began living in rural northern New Mexico and capturing its distinctive culture with his camera. In the text for his 1992 book Red White Blue and God Bless You, Harris wrote, “Just as the old villagers decorate their houses with a devotion that is often religious, the younger people in New Mexico lavish attention on their cars.” Photographing from the vantage point of the car’s driver— looking out the windshield—Harris shows not only the richly appointed interiors but also, importantly, the landscapes they traverse.

A different take on lowriding is offered by artist Rose Simpson, who grew up at Santa Clara Pueblo near Española. As a Native American, Simpson felt a cultural divide between herself and classmates and neighbors outside the pueblo who identified with their Hispano heritage. As an adult, she decided to study automotive science at Northern New Mexico College in Española and to make her own lowrider as a way of exploring that divide. As soon as she transformed herself into a lowrider, Simpson found common ground across cultural as well as gender boundaries. Two photographs by Santa Fe photographer Kate Russell capture Simpson with her lowrider, Maria, while sculptural pieces by Simpson attest to her ongoing interest in the subject.

These artistic tributes confirm what we in New Mexico already know to be true, that lowriders are a distinctive art form in their own right as well as a significant cultural icon that ignites the imaginations of people all over the world. Come join us and be a lowrider for a day, designing your own car (on paper!). In the spirit of the exhibition, take your time…there’s no hurry.

Katherine Ware is curator of photography at the New Mexico Museum of Art, where she organized recent exhibitions including Assumed Identities: The Photographs of Anne Noggle and Self-Regard: Self-Portraits from the Collection. Con Cariño: Artists Inspired by Lowriders runs through October 10, 2016, at the New Mexico Museum of Art.