Forever Young

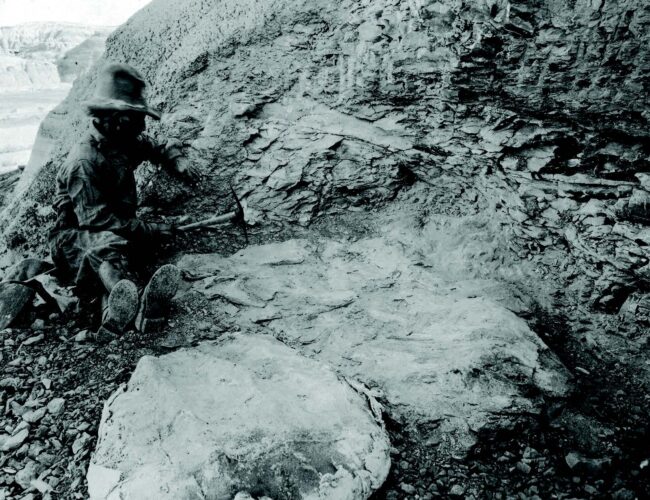

In the 1920s, Charles Sternberg, in his early seventies, collected dinosaur fossils in the badlands south of Farmington in San Juan County. © San Diego Society of Natural History, all rights reserved.

In the 1920s, Charles Sternberg, in his early seventies, collected dinosaur fossils in the badlands south of Farmington in San Juan County. © San Diego Society of Natural History, all rights reserved.

A groundbreaking juvenile dinosaur discovery in northwestern New Mexico enlivens the record.

BY DR. SPENCER G. LUCAS

In July of 2011, a group of paleontologists led by Dr. Robert Sullivan trekked through the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness, part of a month-long project to survey the wilderness for fossils. The paleontologists, from the State Museum of Pennsylvania and the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science (NMMNHS), in Albuquerque, were in one of the country’s most fossil-rich areas. Known to the general public as a haunting, windswept wonderland characterized by its mushroom-capped hoodoos, sculpted bluffs, arches, and slot canyons, it hadn’t been the subject of a paleontology survey for some forty years. Volunteer and student Amanda Cantrell woke up early one day during the final week of the survey, hoping to find something big. Little did she know how big her find would be when she spotted a dark brown area near a sandstone bluff.

In northwestern New Mexico, the area long known as the Bisti Badlands is about thirty-five miles south of Farmington in San Juan County. In 1984 the US Congress established the Bisti Wilderness, including the Bisti and adjacent badlands, an area of about 45,000 acres of federal wilderness managed by the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Most of the wilderness is composed of badlands eroded from rocks of Late Cretaceous age, about seventy-three to seventy-five million years old. Since the 1880s, paleontologists have searched those and other nearby badlands for dinosaurs and other fossils. More dinosaur fossils have come from the Bisti Badlands than from any other area of comparable size in New Mexico.

Today the Bisti Badlands are a desolate but striking landscape in New Mexico’s high desert, more than a mile above sea level and about a thousand miles from the Pacific Ocean. To study the rocks of the Bisti and collect its fossils is to travel not only back in time but to a fundamentally different landscape: a tropical seacoast. The rocks and fossils of the Bisti record an ancient world that has been referred to as “New Mexico’s seacoast,” also the name of the Cretaceous exhibit hall at the NMMNHS devoted to the museum’s fossil record.

During the Late Cretaceous period, the Western Interior Seaway sprawled across the middle of North America, running south–north from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean. For millions of years, the western coast of that sea shifted back and forth across New Mexico. At one time it lay just east of a line drawn through present-day Farmington and Cuba. Far west of the sea, in present-day California, volcanic mountains spewed ash into the sky, and rivers flowed east from those mountains toward the lush coastal swamps and jungles that hugged New Mexico’s ocean shoreline. The rivers teemed with fish, turtles. and crocodiles, while numerous duck-billed and horned dinosaurs roamed the land, eating plants. Predatory tyrannosaurs sat atop the ancient food chain, feeding primarily on the duck-billed and horned dinosaurs.

More than seventy million years later, Charles Sternberg (1850–1943) covered the same ground as the tyrannosaurs and their prey. Considered by most paleontologists the greatest dinosaur collector of all time, he collected fossils throughout the western United States and Canada for about sixty years. He sold his finds to the great natural history museums of the United States, Canada, and Europe; his discoveries can now be seen on display from San Diego to Berlin, Germany.

In 1921 Swedish paleontologist Carl Wiman hired Sternberg to provide dinosaurs and other fossils to populate his rapidly developing displays at the Paleontological Museum of Uppsala University in Sweden. Sternberg knew, from a handful of discoveries dating back to the 1880s, that he could find dinosaur fossils of Late Cretaceous age in northwestern New Mexico.

Motivated and funded, the septuagenarian Sternberg headed to New Mexico, arriving at Chaco Canyon in June of 1921. There he rented a team of horses and a wagon and hired two young Navajo men, Dan Padilla and Ned Shouver, to help him collect fossils. They set out for the nearby badlands, which had eroded into the Late Cretaceous rocks, a terrain at the time little explored by paleontologists. Sternberg found so many dinosaur and other fossils in 1921 that he made two more trips, in 1922 and 1923. During the three field seasons, Sternberg’s discoveries were astounding, and not just in terms of volume (14,000 pounds of Cretaceous vertebrate fossils). Along with fossil turtles and a fossil crocodile skull, he unearthed three skulls and a headless skeleton of a horned dinosaur. He sold the skeleton and one of that dinosaur’s skulls to the Uppsala museum.

After exhausting Uppsala’s buying power in 1923, Sternberg still had plenty of fossils to sell. He lobbied former clients to purchase them, namely the Field Museum of Natural History, in Chicago, and the American Museum of Natural History, in New York. Both museums soon purchased the more interesting New Mexico fossils not sent to Uppsala, including some important dinosaur fossils. The Field Museum bought the skull and skeleton of a duck-billed dinosaur (hadrosaur) from the New Mexico badlands. Regretfully, the fossils sat in storage, unexamined, until the 1960s, when museum scientists identified it as a new species of tube-headed hadrosaur, Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus.

In contrast, the American Museum’s lead paleontologist, Henry Fairfield Osborn, studied the two horned dinosaur skulls immediately. Thus, in 1923, Osborn recognized one of the horned dinosaur skulls Sternberg sold to the New York museum as a new kind of dinosaur that he named Pentaceratops sternbergi. The species name honors the discoverer, one of many fossil species named after Charles Sternberg.

The technical term for “horned dinosaur” is ceratopsian, from the Greek words for “horned face.” The iconic, best-known ceratopsian is Triceratops, named for its three horns. Osborn coined the name Pentaceratops (“fivehorned face”) to recognize the horns above the eyes and nostril, but also two “horns” that project out from the cheeks of the New Mexican dinosaur, which are actually not horns but flanges of the jugal bones. As much as 27 feet (8 meters) long and weighing an estimated 6–8 tons, an adult Pentaceratops was one of the largest horned dinosaurs to have ever lived. Other than an incomplete skull from northwestern Colorado and a recent (and controversial) claim that identifies the dinosaur in southern Canada, all we know of Pentaceratops comes from northwestern New Mexico. Why Pentaceratops was so abundant in New Mexico, and nowhere else, is a mystery to paleontologists.

At present, despite the fact that numerous fossils of Pentaceratops have been found in New Mexico, the most complete skeleton of Pentaceratops known is the one that Sternberg found and sold to Paleontological Museum of Uppsala University, now on display there. Besides the three skulls Sternberg collected, four other nearly complete skulls of Pentaceratops have been found in the Bisti Badlands and nearby badland areas. One skull is on display at the Sam Noble Museum of Natural History in Norman, Oklahoma, and the others are in collections in Lawrence, Kansas; Flagstaff, Arizona; and Albuquerque.

During the 1980s, the NMMNHS borrowed a skull collected by the Museum of Northern Arizona and made a replica of it that is on display. In 2006 a skull collected by the University of Arizona was transferred to the NMMNHS collection. Furthermore, many other bones of Pentaceratops have been collected by NMMNHS museum staff and volunteers over the last thirty years and are now in the fossil collection.

Among the horned dinosaurs that inhabited northwestern New Mexico, Pentaceratops was most common, perhaps living in herds or similar social groups. These huge plant eaters browsed on conifers and primitive flowering plants. When they died, everything from body parts to whole bodies could be buried rapidly in the river channels or along their margins, in swamps or on floodplains. So buried, the dinosaur’s flesh decomposed rapidly; the bones were eventually mineralized to become fossils. Today, these fossils erode from sandstone and mudrock in the Bisti Badlands. Once they reach the surface, the fossil bones can be spotted and collected by paleontologists like Amanda Cantrell.

The dark brown area she spotted near a sandstone bluff in July 2011 was made up of the protruding bones of a juvenile Pentaceratops skull, the edges of the frill, and some exposed limb bones and ribs. The skeleton is the first juvenile specimen of the dinosaur known to science. If we estimate the dinosaur’s size based from the length of its thighbone (femur), the juvenile Pentaceratops is about 70 percent of the size of an adult. Although news reports called it a “baby” Pentaceratops, perhaps “teenager” is a more accurate term.

Looking at the fossil soon after it was discovered, I knew this was an important fossil scientifically—an exciting discovery. I also knew much work lay ahead. NMMNHS’s permit to “surface collect” fossils in the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness would not cover the epic excavation this dinosaur fossil would require. We would have to secure an excavation permit from the BLM and then wait a few months for an environmental assessment of the impacts of excavating the site. I also knew there was a chance that the only bones present were those we saw, not the whole skeleton we hoped for.

The excavation crew consisted of NMMNHS staff members and many more volunteers; ultimately, about twenty people worked on the excavation over several trips. The work was slow and arduous. The crew brought all tools, water, and plaster to the excavation site on foot, a hike of well over a mile. The sandstone containing the juvenile dinosaur skeleton had the consistency of concrete, and much pounding with hammer and chisel was needed to cut channels around the fossil bones.

The excavation crew delineated two large (more than one ton each) blocks of rock that contained the dinosaur bones. I breathed a sigh of relief when the excavation revealed much of the skeleton of the young dinosaur was indeed there, buried in hard sandstone.

Digging underneath the blocks made them into mushroom shaped pedestals that were then covered with a layer of wet paper, followed by layers of plaster-soaked strips of burlap. Like the cast a doctor puts on a broken bone, the plaster jacket so created encases the fossils to protect them on their journey to the museum. The base of each block was then cracked, and the blocks were rolled over. This way the remainder of the blocks could be covered with paper and plaster-soaked burlap strips. The totally encased blocks, juvenile dinosaur inside, were now ready to travel to the NMMNHS.

However, once excavated, the two plaster jackets were too large to be carried out. The only practical solution was to have them airlifted by helicopter. And about the only helicopter around that could lift such a load belonged to the US National Guard.

I approached the National Guard with some apprehension, but they agreed to give it a shot. Much paperwork needed to be prepared and sent all the way up the line to the Pentagon for approval, but the process went off without a hitch. On October 28, 2015, a Black Hawk helicopter flew from Santa Fe to the Bisti and lifted the juvenile dinosaur, snug in its plaster jackets, to deposit it on the guard’s flatbed truck, which took it to the NMMNHS. This took two trips because one of the plaster blocks had cracked due to rain and weather, and had to be repaired before the helicopter could return to lift it. The helicopter also lifted a third, huge block containing an adult skull of Pentaceratops from another badlands area about ten miles from the Bisti.

Much is known about how ceratopsian dinosaurs grew during their life cycle. Most famous are the different stages, from baby to adult, of Protoceratops, discovered in Mongolia during the 1920s by the famous Central Asiatic expeditions of the American Museum of Natural History. These fossils, and other juvenile fossils of ceratopsians, show that the skull—particularly the shape and size of the horns—changed dramatically as the dinosaur grew. However, we’ve known nothing about such changes during the life of Pentaceratops, simply because nobody had ever found a fossil of a young one until now. The skeleton that Cantrell found promises to give paleontologists their first direct insight into the life cycle of Pentaceratops.

How did that juvenile Pentaceratops die? I could see when the sandstone block was excavated that the bones are no longer connected, but closely associated, concentrated in a layer of sandstone, which has textures (bedding) indicative of flowing water. Such sandstones, common in the Bisti, are known to be the deposits of ancient river channels. Clearly, the juvenile dinosaur’s body had decomposed somewhat before the carcass, much of it still held together by soft tissue, was washed down the ancient river course to arrive at the place where it would be collected, millions of years later.

It is almost impossible to look at a fossil like the skeleton of the juvenile Pentaceratops and determine how the animal died. This is simply because most causes of death do not leave a mark on the skeleton, and the fossilized bones are all we find. Thus, all we can say about the juvenile Pentaceratops is that it died, cause unknown, about seventy-three million years ago. Whether disease, an accident, or a predator killed the dinosaur may never be known. Its body must not have been buried immediately, and some decomposition (and perhaps scavenging) took place. Something like a hard rain washed the body into a river, where it traveled an undetermined distance before it was buried in sand to become the fossil we collected.

Now that it is in the museum, the preparation of the juvenile skeleton of Pentaceratops has begun. This is being done in the museum’s FossilWorks exhibit, a fossil-preparation lab visible to the public. To a paleontologist, preparation means the painstaking process of removing the rock that encases the fossil bones, stabilizing the bones, repairing any fractures, and removing the bones from the plaster jacket. One or two volunteer preparatory will undertake most of the work. We will finally be able to say how complete of a skeleton was collected. I expect that process to take at least one year.

Once the preparation is complete, we will study the juvenile dinosaur skeleton to write and publish our research results. We will mostly focus our research on comparing this juvenile skeleton to the adult skeleton Sternberg sold to the Uppsala museum, and to the juvenile and adult skeletons of other ceratopsian dinosaurs. Differences and similarities will tell us much about whether Pentaceratops grew like other ceratopsians. The fossil will also be added to the exhibits of the NMMNHS to teach the public about this young dinosaur and its world.

The whole process, from Cantrell’s discovery to research, publication, and display, will last about six or seven years, which seems like a long time. But when you compare it to the seventy-three million years that the juvenile Pentaceratops skeleton was in the earth before being discovered, excavated, flown by helicopter, driven by truck, prepared, and finally exhibited in a natural history museum in Albuquerque, it’s just the blink of an eye.

Dr. Spencer G. Lucas is the curator of geology and paleontology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

THE BIG REVEAL FRESH EYES FIND THE FOSSILS OF A YOUNG DINOSAUR.

BY MARY ANN HATCHITT

One of the first things you notice about Amanda Cantrell is her eyes; almost teal in color, they are clear, sharp, and focused. And it is her vision that the modest young paleontologist credits with the discovery of the first juvenile Pentaceratops skeleton ever recovered, during a survey in the Bisti Wilderness, south of Farmington, New Mexico.

Cantrell, her fiancé, Tom Suazo, and UNM undergraduate student Joshua Fry were part of a New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science (NMMNHS) team performing a three-week survey in the summer of 2011, led by Dr. Robert Sullivan, the senior curator emeritus of paleontology and geology at the State Museum of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, and research associate at NMMNHS.

“It was the best month of my life,” Cantrell said. “I brought all my camping gear, and on the weekends we’d come home to refill water and supplies. We were spending four and five days at a time out there, combing the hills, documenting everything we found.”

Early one morning during the last week of the survey, Cantrell said, she was “eager to make the digging this day count for something. Then Bob [Sullivan] sent us up on a hill, all together.” She scanned the rough, dry, desolate desert terrain and noticed something dark brown in a sea of beige near a sandstone bluff.

“I walked right to it,” she said. It was the frill of a dinosaur skeleton—the bony, platelike structure that forms the back of the skull of horned dinosaurs.

“We knew it was must be an important discovery when Bob joined us and he was excited by the find,” Cantrell said. “He knew right away it was a Pentaceratops. He recognized that it was very small, a juvenile.” Two bones of the skull, the edges of the frill, episquamosals (small triangular segments fused to the frill), and some exposed teeth and vertebrae were visible.

Sullivan, who has been going to the San Juan Basin since the 1980s, called the expedition a routine dig. He says finding the Pentaceratops skeleton was “one of the most important discoveries in recent years.”

Cantrell and Suazo were bitten by the paleontology bug about a decade earlier, when they stumbled upon ancient fossils while on dates in the great outdoors. “The first fossils we found were brachiopods—ocean-life shells—in the Sandia Mountains. Later we found ammonites along the Rio Puerco. We were both in school trying to decide what to do with our lives, and we looked at each other after finding the fossils and said, ‘How do we do this as a career?’”

A student at Central New Mexico Community College at the time, Cantrell knew she needed to get a geology degree, and a savvy professor directed her to Dr. Spencer Lucas, chief scientist and curator at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science for guidance on pursuing a career in paleontology. Amanda enrolled at the University of New Mexico and became an intern and volunteer at the NMMNHS lab. She was still a student and volunteer when she discovered the juvenile Pentaceratops.

The next week, Sullivan brought Dr. Spencer Lucas, curator of paleontology at NMMNHS, to the site “because we knew we were going to need help figuring out how to retrieve the fossils. It was too big to handle alone, and we knew we needed help getting it out of the wilderness.” Lucas began the process of securing permits from the BLM to excavate the fossils and transport them to the NMMNHS, in Albuquerque. (He is the author of “Forever Young,” in this issue.)

“I can’t underscore enough how important it is from a scientific standpoint to have a juvenile ceratopsian from the San Juan Basin,” said Sullivan. “This one, because of its potential completeness, has a great potential for giving us a lot of information about the growth of these dinosaurs.”

The juvenile Pentaceratops skull was unveiled in a public viewing at the FossilWorks exhibition at the museum in early November 2015. It will remain on display throughout 2016 as staff clean and stabilize it.

This is the work that Amanda Cantrell returned to at the end of her maternity leave. She and Tom Suazo welcomed their first child, Kellach Day Suazo, on February 1, 2016. One of the first things you notice about him is that he has his mother’s eyes. His parents will surely give him every opportunity to develop a passion for dinosaurs.

Mary Ann Hatchitt is the communications director of the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs.