Ages and Stages

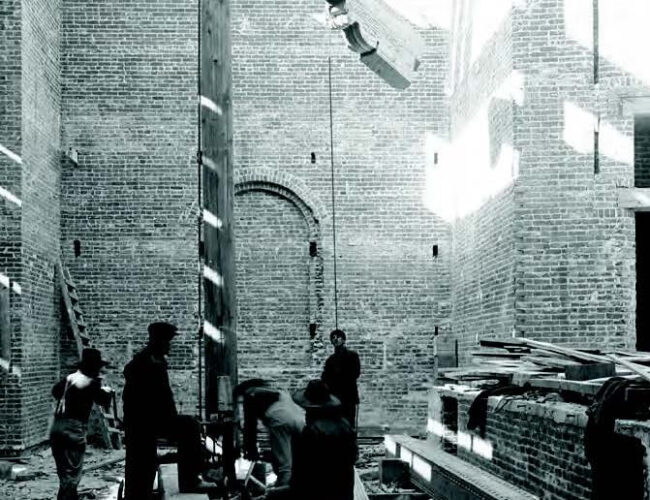

St. Francis Auditorium under construction, Museum of Fine Arts, Santa Fe, New Mexico,1917. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives

St. Francis Auditorium under construction, Museum of Fine Arts, Santa Fe, New Mexico,1917. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives

BY LYNN CLINE

The Museum of Art’s St. Francis Auditorium— a sanctuary for the soul of Santa Fe—turns 100.

Sunday evening, November 25, 1917. The old Algodones bell rings out from the Acoma tower of Santa Fe’s new art museum, announcing the dedication hour. All of New Mexico, it seems, has turned out to celebrate the city’s latest crown jewel. A sea of people throngs the massive adobe building, inspired by seventeenth-century Spanish Missionstyle churches in New Mexico. Inside, the 450-seat St. Francis Auditorium is packed with 1,200 guests, who break out into a rousing chorus of “America” as the celebration begins.

This is wartime, after all, and some of the men who were instrumental in building the museum are now in Europe, fighting. Essential building deliveries were delayed for months. And yet, despite the setbacks, the new museum—designed by architect Isaac Hamilton Rapp and his firm— is about to open. The auditorium crowd, seated on wooden pews and filling the choir loft, is eager for the festivities to begin. As people admire the glowing murals devoted to St. Francis of Assisi, the Honorable Frank Springer—lead museum supporter and New Mexico entrepreneur—takes the stage. Stepping to a wooden lectern, he begins to read from his notes. . .

A century later, that same lectern—handcrafted by archaeologist and museum construction supervisor Jesse L. Nusbaum, who made much of the original furniture in the museum—still stands on the auditorium stage, present for countless entrances, exits, set changes, standing ovations, recitals, and rehearsals, along with community celebrations of life’s milestones.

“What amazed me when I came here is how the St. Francis Auditorium is such a beloved place,” says Mary Kershaw, director of the New Mexico Museum of Art. “It’s such a civic center that it hosts graduations, weddings, memorial services, and all kinds of cultural events. The venue has its own identity. People know the St. Francis Auditorium. My goal is for them to know that the auditorium is part of the museum.” From the start, the auditorium has been a part of the community as well, a sanctuary—museum founder Edgar Lee Hewett once said—for New Mexico’s unique history, art, culture, and heritage. “The museum founders were extremely far sighted, because museums today are striving to become part of civic life and centers for civic discourse,” says Kershaw. “That they had the foresight to create this civic center a century ago was a real innovation, and it was in response to the needs of the community—there wasn’t anything like that here yet. Museums often are built around a collection, but this museum was different. It was built for what it could be in the community and for what it could help the community become.”

One hundred years later, the auditorium remains an integral part of the Santa Fe community. It’s biggest event of the year is a treasured community tradition that dates back more than eighty years: the annual Holiday Open House, which features performances by acclaimed Santa Fe artist Gustave Baumann’s troupe of hand-carved marionettes. The Baumann Marionette Christmas Show debuted in the auditorium in 1932, with Baumann operating the marionettes and his wife, Jane, performing from the scripts they wrote together. It now draws an audience of 800 to 1,200 people every year, including generations of families who consider it to be an integral part of their unique Santa Fe holiday celebration.

Across the decades, speakers from around the country, from artists and authors to politicians, composers, and other luminaries, have stood behind the lectern on the St. Francis Auditorium stage. The New Mexico Legislature held a memorial service there for Theodore Roosevelt in 1919, and it’s been the inauguration site for many New Mexico governors. Poet Robert Frost gave a lecture, likely at the lectern, on August 5, 1935, followed by a luncheon at the rambling adobe home (now the Inn of the Turquoise Bear) of poet Witter Bynner, a prominent member of the Santa Fe writers’ colony. The two reportedly got into an argument, probably sparked by Bynner‘s envy of Frost’s success, and Bynner famously dumped a beer over the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet’s head. Not surprisingly, Frost never returned to Santa Fe.

The St. Francis Auditorium also has been the scene of much drama, in the form of theater groups staging a variety of plays. The fledgling Community Theater—founded by Santa Fe writers’ colony author Mary Austin—drew rave reviews for its 1919 production of a medley of plays illustrated by Baumann’s scenery. The Drama League of the Santa Fe Women’s Club’s 1921 performance of Grumpy featured Taos Society of Artists painter B.J.O. Nordfeldt in the title role. In 1925, the Santa Fe Players premiered Knives from Syria, by American author, poet, and playwright Lynn Riggs, whose 1930 Broadway play Green Grow the Lilacs was the basis for the musical Oklahoma!

Knives from Syria—about a Syrian peddler selling exotic goods to women in remote southwestern towns—captivated the audience: “Carved wooden beams supported the room’s high ceiling, and the stage protruded into the room, without a front curtain,” writes Phyllis Cole Braunlich in Haunted by Home: The Life and Letters of Lynn Riggs. “Arched religious tapestries, like stained-glass windows, hung high on the white walls. Patrons sat on heavy wooden pews. The place lent a quaint dignity to Rigg’s brief play, which. . . continued to be popular with amateur drama groups as late as 1956, when it had been given a total of 134 performances in thirty-six states.”

Some of the country’s most influential artists have also stood at the auditorium’s lectern, presenting talks coinciding with museum exhibits of their work. Native American painter Fritz Scholder took the stage in 1975, as did American abstract painter Agnes Martin in 1989. In 2012, American feminist artist Judy Chicago took part in an onstage conversation with Merry Scully, the museum’s head of curatorial affairs. Musicians and classical music groups praise the St. Francis Auditorium’s sound quality. As the Santa Fe New Mexican reported on February 2, 1917, “Experiments indicate the acoustics of the new auditorium, with its ceiling of heavy wooden beams and ‘herring-bone’ thatching of seasoned spruce sticks brought from the ‘burns’ on the Sangre de Cristos, will be extremely good, the construction tending to cause absorption of vibrations. The thatching is from sound dead trunks of trees ‘suffocated’ by forest fires, the ends of the needles being burned without charring the tree, and causing it to die.”

The acoustics were so good that composer Aaron Copland stopped by to practice the piano during a 1929 visit to Santa Fe, and local and visiting musicians regularly presented concerts in the venue. There was just one thing missing: the organ, which the founders had included in the building plans. “Who will give the organ for the St. Francis Auditorium in the new Museum?” the New Mexican beseeched in an October 30, 1916 article. “Place for it has been provided but no funds are available for its purchase. Music is to be cultivated as much as art, architecture, and archaeology in this temple to St. Francis, for St. Francis, above all, was a lover of music.”

The organ arrived twenty years later, when Mr. and Mrs. James McNary of El Paso, Texas, donated a full-concert pipe organ that was in their home, which had just been sold. The couple made the donation in memory of Mrs. McNary’s father, New Mexico banker Joshua Reynolds. The St. Francis Auditorium subsequently held special meaning for the family, as two generations of McNarys were married in front of the organ—daughter Ruth McNary in 1938 and grandson Graham R. McNary, Jr. in 1954.

The donation of the organ ushered in a new musical era for the auditorium, as chamber music festivals, music appreciation classes, and other musical events became part of the regular programming. Igor Stravinsky’s biblical drama The Flood premiered here during a 1962 festival honoring the composer’s eightieth birthday. A decade later, the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival was founded and the group has performed in the venue every summer since during its six-week season.

“One of the things that that makes the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival so unique is the place where the concerts are being held,” says Steven Ovitsky, the festival’s executive director. “The museum courtyard, as a gathering place before the concert and during the intermission, adds to the remarkably wonderful nature of going to concerts at the festival. So, from the courtyard to the auditorium, the programming is enhanced and made unique by that location. It’s like hearing the Vienna Philharmonic in the Musikverein—that hall is a special place. You can go to many other cities and find a nice hall with good acoustics, but when you go to the St. Francis Auditorium, it’s truly of our place, and it makes the concert a concert that can only can happen here, even though it may be music by Beethoven, Mozart, or Copland.”

The St. Francis Auditorium also serves as an inspiring setting for the annual presentation of the Governor’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts, established in 1984 by Governor Bruce King and First Lady Alice King to honor New Mexicans who have made significant lifetime contributions to the arts. Recipients include Judy Chicago; actor and director Robert Redford; actor Wes Studi, author George R.R. Martin; artists David Bradley and Peter Hurd, and many other artists, art educators, and philanthropists.

Award-winning Santa Fe author Carmella Padilla received her New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts in the auditorium in 2009. “The governor’s award was a highlight and, in some ways, a coming full circle for me, in terms of growing up here and then being honored for contributing to the art and culture scene here,” Padilla says. “And that was an honor and a privilege, just being in that space.”

Padilla carries another cherished memory of St. Francis Auditorium from her days at Santa Fe High School, where she sang in the choir, then directed by longtime choral teacher Mary Linda Gutierrez. “Every year, we’d prepare for our Christmas concert in St. Francis Auditorium,” she says. “It would always draw a packed audience. It was very staged and pageant-like. We wore white gowns, and the concert would start with all the lights turned off, and we walked in holding candles and singing ‘Carol of the Bells’ or ‘Adeste Fideles.’ Gutierrez really instilled in us the idea that this was an important cultural space, an historical space and a beautiful space for something special.”

Padilla recalls that when Perry Como visited Santa Fe in 1979 to tape the Perry Como’s Christmas in New Mexico television show, he recorded a segment at the St. Francis Auditorium. “He filmed on the Plaza and in different parts of the city, and he sang with our choir in the auditorium, so we were on the show.”

The high school Christmas concerts reflect earlier performances at St. Francis Auditorium of Christmas cantatas and traditional folk plays, such as Los Pastores, a medieval Spanish shepherd play, and the Vision of our Lady of Guadalupe, a Mexican miracle play. Over the years, the venue’s programming has evolved, keeping pace with the times and offering innovative events, such as an evening with Zen master and calligrapher Haradi Rochi, from the Tahoma Sogenji Zen Monastery on Whidbey Island, Washington, who gave a talk and demonstration on his craft in 2013. Often, lectures by prominent authors and historians focus on the artists and writers who once presented talks in the auditorium.The St. Francis Auditorium has indeed fulfilled Hewett’s vision of a “sanctuary” for culture, history, and heritage, as well as for the community. In 2015, a memorial service for James Beard Award-winning author Bill Jamison brought family and friends together to celebrate his life in a sacred space.

“St. Francis Auditorium was my husband Bill’s choice for his memorial service,” says Cheryl Alters Jamison. “Both of us spent a number of years working in the arts here in Santa Fe, and we both loved the New Mexico Museum of Art and had long appreciated the architectural work of Isaac Hamilton Rapp. We had seen events from chamber music to Texas musician-artist Terry Allen there. The lofty ceiling, the rustic wood, the plastered walls, the filtered light, the acoustics for our musician, David Manzanares—all made it a memorable setting for the 400 friends and family who attended a service that we wanted to be a celebration of Bill’s life. I felt a great sense of power and comfort there.”

The venerated auditorium’s remarkable history is palpable and visible, right down to the wooden lectern, which almost didn’t make it to the stage. Nusbaum, it turns out, initially made the piece for Springer to use in his office as a reading desk, where he could display a miniature painting that his daughter had made. Just before giving his dedication speech, however, Springer decided to use the lectern to hold his notes, and it’s been part of the scenery ever since. And the old Algodones bell, which once belonged to former Governor Miguel A. Otero and, according to the New Mexican, was cast in Spain many centuries ago, still rings today, for weddings and wakes.

“The auditorium is such a well-used place,” Kershaw says. “Because of that, it’s never too early to reserve a date. Interestingly, the venue is not that well-equipped—we have to bring in technology and it hasn’t got a green room for performances. It was built, really, as a lecture hall and it lacks a lot of modern infrastructure. You would think that with these shortcomings, the space would be struggling, but it’s the opposite. I love that people use the auditorium so much. I think it’s magical.”

Lynn Cline is the Santa Fe author of the award-winning The Maverick Cookbook: Iconic Recipes and Tales from New Mexico and Literary Pilgrims: The Santa Fe and Taos Writers’ Colonies, 1917–1950. Her travel guide, Romantic Santa Fe, will be published this fall.