¡Buenas Melodías!

Four centuries of New Mexican music tune up for an epic show.

Electric guitar by Eugene Santillanes. Carlsbad, New Mexico, 2018. Wood, metal, paint. 39 ¾ × 12 13 ⁄16 × 2 ¾ in.

Museum of International Folk Art, IFAF Collection, FA.2018.68.1. Photograph by Carrie Haley.

Electric guitar by Eugene Santillanes. Carlsbad, New Mexico, 2018. Wood, metal, paint. 39 ¾ × 12 13 ⁄16 × 2 ¾ in.

Museum of International Folk Art, IFAF Collection, FA.2018.68.1. Photograph by Carrie Haley.

BY NICOLASA CHÁVEZ

Música Buena: Hispano Folk Music of New Mexico, at the Museum of International Folk Art from October 6, 2019, to March 7, 2021, tells the history of New Mexican Hispano folk music (and related dramatic interpretations) that developed over four hundred years, from the Colonial era to the present day. Master musician and instrument maker Cipriano Vigil, recognized by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Smithsonian Institution, serves as guest curator; his book New Mexican Folk Music: Treasures of a People (University of New Mexico Press, 2014) was a catalyst for the exhibition.

When the Spanish arrived in the Americas, they brought musical traditions that developed from their multicultural history, including Celtic, Christian, Muslim, Roman, Sephardic, and Visigoth influences. New traditions formed as Spanish influences blended with regional Native practices, creating a distinct Nuevo Mexicano genre, unique within the United States and in the Spanish-speaking Americas. The exhibition also examines how these musical styles have survived amid the influx of imported sounds during the twentieth century.

Música Buena includes items from MOIFA’s extensive collection, digital footage from the archives, new videos created specifically for the exhibition by Wisdom Archives, items from Vigil’s private collection, and live performances.

Visitors will experience several distinct sections representing musical genres and themes. Each section contains video stations, along with instruments, costumes, and memorabilia. Upon entering the gallery, visitors find themselves in a traditional dancehall setting, complete with a nineteenth-century tin araña (chandelier) and benches on opposite sides, harking back to when men and women sat on opposite sides of the room, and men walked across the room to ask young women to dance.

Following the dancehall is a display of instruments traditionally used in Hispano folk music. Many were created by hand by unknown artists from found and recycled materials: a nineteenth-century homemade violin, an armadillo-shell guitar, and an original hand-carved matraca (noisemaker) by the grandfather of the Cordova woodcarving style, José Dolores López. Other beloved instruments include pitos (flutes) made of wood, bone, PVC piping, and an empty bullet cartridge.

+ + +

Entriegas are songs that represent various or rites of passage or stages of life such as birth, marriage, and death. Songs for birth and marriage are performed in a ceremony that includes the entire community. The new parents, godparents, or newlyweds would make their vows before God and before their community, and the community would vow to help, support and protect the baby, couple, or family. The entriega de la muerte, or death entriega, incorporates alabados, songs of prayer and devotion that are performed only during Holy Week processions—or at funerals, when alabados ask the soul to be received in Heaven. Representing these traditions are a wooden baby cradle from the 1930s by furniture maker Sam Huddleson, a nineteenth-century wedding gown and head wreath of orange blossoms on loan from the New Mexico History Museum and Palace of the Governors, and an original book of alabados.

Another seasonal rite of passage is the annual cleaning of the acequia (irrigation ditch), completed with the accompaniment of song. Several of these songs stream through the exhibition as ambient sound, their words translated above a nineteenth-century grain chest and other agricultural tools.

+ + +

New Mexican dramatic traditions including music and dance comprise the largest section of the exhibition. During the Colonial period, both liturgical and secular customs flourished. Theatrical reenactments, passed from generation to generation, developed over time, becoming innovative New Mexican versions.

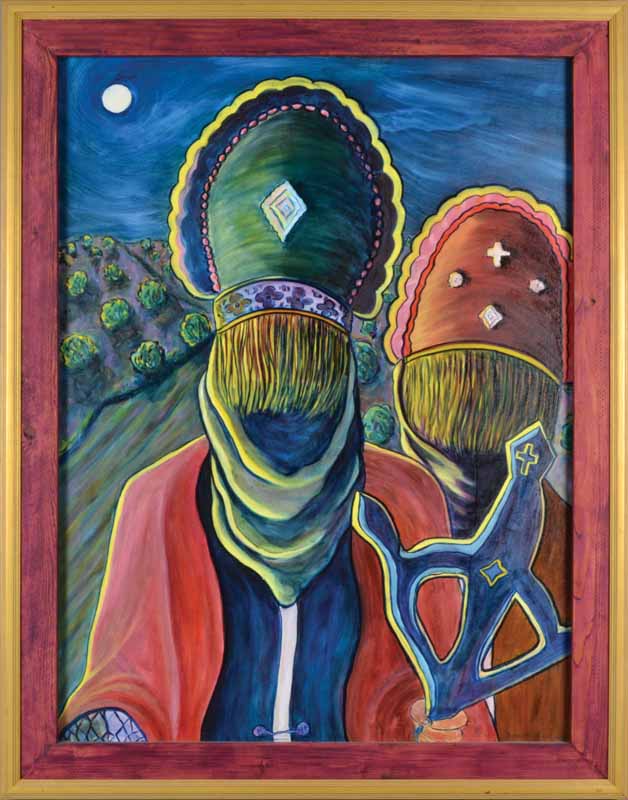

Danza de los Matachines has been performed by Hispano, Pueblo, and Genízaro populations for several centuries in New Mexico. The dance is also performed in Mexico and Guatemala. In New Mexico, the dances take place each year during holidays and on special feast days all over the state. The exhibition includes several Matachines headdresses and costumes from both Mexico and New Mexico, along with a selection of palmas (dance wands), rattles, and other works related to los Matachines.

Moros y Cristianos is considered the oldest and longest- running play in the continental United States, and also the earliest play performed entirely on horseback. It was performed in New Mexico for over 400 years, from 1598 until the end of the twentieth century. The dramatization includes the reenactment of the many battles and changing of hands between Christian and Muslim rule throughout Medieval Spain. Including musical themes of both Christian and Arabic traditions, the play acknowledges and celebrates Spain’s multicultural heritage during the time of the Reconquista. The dramatization was preserved by Josie and Percy Luján in Chimayó; they also conducted a reenactment at the Smithsonian Institution’s annual Folklife Festival. Family members have kindly lent original costumes and video footage for Música Buena.

Los Pastores and Las Posadas are both holiday traditions that have been performed in New Mexico and all over the Americas since the arrival of the Spanish. La Gran Pastorela (The Great Shepherds Play) is the tale of shepherds on their way to see the Christ child after his birth. The character of El Demonio, or the Devil, plays tricks and tries to interfere with their journey and scare them along the way. Las Posadas re-enacts Joseph and Mary’s journey for shelter so that she may give birth. A group of singers accompany Mary and Joseph, traveling from house to house, asking for shelter. The owners act as innkeepers, chanting “No” and turning them away. One final stop, representing the manger, lets the group in, where feasting and singing ensues.

A more recent version of Las Posadas, held for the last forty years, is performed around the Santa Fe Plaza. The innkeepers are represented as devils who turn Joseph and Mary away, and the couple is finally let in to the courtyard of the Palace of the Governors, representing the manger.

Música Buena displays one of the original devil costumes from a Los Pastores production from 1915. The costume resides in the New Mexico History Museum’s collections, and an original photograph of the man dressed in the same costume is held in the Museum of International Folk Art’s archives.

The traditions of Dar los Días, or Día de los Manueles and Los Comanches de la Serna are performed each year on New Year’s Day. Reminiscent of old European Mummer’s Plays, Dar los Días is celebrated by a group of musicians traveling from house to house singing New Year’s blessings to homeowners who then let the group inside for merriment and feasting. During the course of many songs and verses, which include the names of everyone present so that each person may be blessed for the New Year, the group also performs a symbolic killing of the old year.

Los Comanches celebrates the rare occasion when Spanish settlers and Pueblo Natives came together to protect New Mexican land from invading forces, often the Comanches. There are several versions: One is conducted as a dramatization on horseback, similar to that of Moros y Cristianos, and depicts actual historical events in which Cuerno Verde, the leader of the Comanches, was defeated. The other is entirely conducted via ritual music and dance. In Ranchos de Taos, Genízaro dancers, who are of Hispano and Comanche blood, re-enact the Comanche dances, drumming and performing door to door to families throughout the village to ring in the New Year.

+ + +

Twentieth-century imports like mariachi, Latino rock, flamenco, and cumbia have become a part of New Mexico’s rich musical heritage, almost replacing the earlier New Mexican songs at public fiestas and bandstands across the state. The exhibition closes with a discussion of the survival and development of New Mexican Hispano folk music in light of newer imports gaining popularity within its cultural milieu.

Contemporary musical instruments that show off the talent and innovation of New Mexican artists are on display, with fiesta costumes representing public events in which New Mexican Hispano music survives. Gems from Cipriano Vigil’s massive 300-instrument collection include an aluminum guitar, a glass guitar, a cigar box electric guitar, and another made from recycled New Mexico license plates. Another contemporary piece is a hand-carved electric guitar by Contemporary Hispanic Market artist Eugene Santillanes, who learned the craft from his son, a heavy metal musician. Two video stations are dedicated to contemporary performance and musicians and scholars dedicated to the continuance of Hispano folk music today.

In addition to the museum exhibition, archival footage from the Bartlett Library and Archives will also be available online. Musicians will perform in the gallery at special events throughout the run of the exhibition.

Nicolasa Chávez is a fourteenth-generation New Mexican and the curator of Contemporary Hispano & Spanish Colonial Collections at the Museum of International Folk Art. She recently curated Flamenco: From Spain to New Mexico and is the author of the accompanying publication.