Hides in Plain Sight

Historic Hide Paintings Tell Stories of Art, Battle, and Colonization

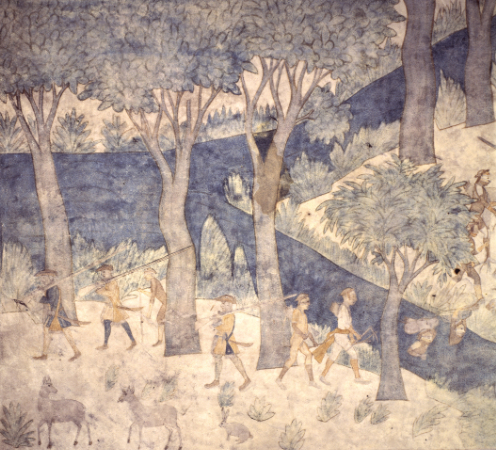

Segesser II (left side detail), ca. 1720–1729. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA),

Neg. No. 158344; Palace of the Governors artifact no. 11005/45.

Segesser II (left side detail), ca. 1720–1729. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA),

Neg. No. 158344; Palace of the Governors artifact no. 11005/45.

By Rick Hendricks

Historians and buffs of the Plains and the Southwest likely know the tragic story of the denouement of the Villasur expedition, which departed Santa Fe on June 16, 1720, in search of French soldiers on the eastern plains.

Taking the field was a small force consisting of approximately forty-two mounted soldiers, sixty Pueblo allies, an unknown number of Apache guides, and a Franciscan friar. The disastrous encounter between the troops from New Mexico and what is believed to be a combined force of Pawnees, Otoes, and French took place on August 14, 1720, at the confluence of the Loup and Platte Rivers in present-day Nebraska. The grim reckoning of casualties indicated that many New Mexican men lay dead on the plains, and just over a dozen made it back to Santa Fe to recount the battle.

Not just the subject of books and oral history, the expedition is also chronicled on the Segesser hides, two very large paintings on animal hides that were stitched together to form a canvas. Although it is astounding that the hide paintings have survived for almost three centuries and that their violent narrative can still be read, by the early twenty-first century, they were in need of some tender loving care.

When the Museum of New Mexico reopens the Palace of the Governors following extensive renovation, the Segesser hides will have a new home in state-of-the art, environmentally controlled cases.

In order to provide the care required by such a unique artifact, a special kind of doctor was needed. The Museum of New Mexico found him in the person of Mark MacKenzie, a native of Canada. When confronted with the challenge of the Segesser hides, MacKenzie, who recently retired as director of the Museum of New Mexico Conservation Department, remarked that he was pursuing two conservation goals. First, there was the need to preserve the centuries-old hide paintings by gaining an understanding of how they were aging to know how best to preserve them. Second, there was much information waiting to be discovered through a thorough scientific examination.

Background on the Segesser Hides

The events of that August day in 1720 took place in two very different contexts. In the view from New Mexico, Spain was seeking to halt French penetration into its territory. Rather than achieve this aim, the expedition was an utter failure and marked the end of Spanish expansion north of New Mexico.

Neg. No. 149799; Palace of the Governors artifact no. 11004/45.

From the Pawnee perspective, their world was changing; they felt pressure on their traditional lands from Siouxan Dakotas from the east, the arrival of the Otoes in the area, and Comanche and Apache expansion from the west. Moreover, the Pawnees viewed Spaniards as allies of the Apaches, their traditional enemies. The Pawnees responded to these pressures with a general movement west and south, relocating to hilltops along the Loup and Platte Rivers. The Otoes established villages in the same area, filling in gaps between Pawnee villages. Finally, the Pawnees formed a strategic alliance with the French. Annihilating the New Mexican troops effectively eliminated a dangerous ally of the Apaches.

No one knows why the hide paintings were made. The narrative of Segesser II clearly relates a massacre of New Mexican troops at the hands of Pawnees, Otoes, and French. This suggests Governor Antonio Valverde Cosío as a likely patron. He was probably the wealthiest man in New Mexico in the 1720s, and because he was roundly criticized for sending the inexperienced Villasur in command of the expedition, he had reason to show that the New Mexican troops were badly outnumbered by enemies with superior firepower. In defending himself, Valverde always insisted on French involvement in the massacre—although this cannot be corroborated in French sources. Where the hides were made and how they made their way to Sonora, Mexico, are queries still in search of definitive answers.

What is beyond question is that the hides came into the possession of the priest Philipp Anton Segesser von Brunegg, SJ, who served in Jesuit missions in the Pimería Alta. In 1758 he sent three “colored skins” to his brother in Switzerland. There is no consensus on the scene that appears on Segesser I. Some scholars believe it depicts one of Valverde’s several punitive expeditions onto the Buffalo Plains, since there are bison in the painting. Segesser II is a narrative of the Villasur expedition. There are no images or descriptions of Segesser III. All that is known with respect to this third hide is that it arrived in Spain with the other two.

Dr. Gottfried Hotz of the North American Native Museum in Zurich learned of the hides in 1945 when they were still in the possession of the Segesser family. Hotz corresponded with Dr. Bertha Dutton, curator at the Museum of New Mexico, beginning in 1960. E. Boyd, curator of Spanish Colonial art at the Museum of International Folk Art, along with Oliver LaFarge, campaigned for the hides to come to New Mexico for an exhibition. New Mexico History Museum Director Dr. Tom Chávez traveled to Zurich in 1985, and the Museum of New Mexico’s Board of Regents and the Museum of New Mexico Foundation requested an eighteen-month loan of the Segesser hide paintings. The hides arrived in Santa Fe in 1986, and two years later, by means of an emergency appropriation by the state Legislature, the State of New Mexico purchased them from Dr. Andre von Segesser.

Multispectral Imaging

MacKenzie was interested in the possibilities of multispectral imaging for revealing information about the Segesser hides. Multispectral imaging, as the name implies, involves breaking the light spectrum into multiple bands beyond the RGB (red, green, and blue) of the visible spectrum. Multispectral imaging can extend into ultraviolet (shorter wavelength, higher frequency) or out to near-infrared (longer wavelength, lower frequency). False color images make it easier to discern features that are not easily discernable in visible RGB.

In 2012, MacKenzie formed a pilot project with Michael B. Toth, president of R.B. Toth Associates in Bethesda, Maryland. Toth brought his hyperspectral imaging equipment to the museum. Also participating were Dr. Fenella G. France, chief of the Preservation Research and Testing Division of the Library of Congress, and Dr. Eric Hansen, the former holder of the same position.

The exciting results of the visit of specialists inspired MacKenzie—a creative and skillful gadgeteer—to build a camera for the Museum of New Mexico. Because the hides measure 54 inches by nearly 18 feet, a simple camera would not suffice. The result was what MacKenzie liked to call “Franken-Camera.” The equipment consists of an imaging gantry that can travel 8 by 6 feet horizontally over a bed where the Segesser hides rest while being examined. The camera has 2 feet of vertical travel over the bed and has .001 inches of positioning accuracy controlled by a computer program. The camera is capable of taking 3,817 images for the project. As an example of the data that were collected, the imaging of Segesser I at RGB and other wavelengths from ultraviolet to infrared produced a mosaic of 8.1 gigapixels (a gigapixel is a digital image bitmap composed of one billion pixels). The project produced more than 4 terabytes (a terabyte is 1 trillion bytes) of data.

The imaging study provided a wealth of information about the pigments used on the hides and what the original colors looked like. It also revealed drawings and patterns invisible to the naked eye. This showed how the artists made alterations to the underlying plan for the narrative image, such as repositioning a horse’s head. Importantly, the study also suggested something about how the paintings were made.

European and Native Artists

The deep dive below the surface of the Segesser hides has led to a solid hypothesis regarding how they were produced.

Father and son Tomás and Nicolás Jirón de Tejeda were guild-trained master painters in Mexico City before they joined Diego de Vargas in the recolonization of New Mexico of 1693. Nicolás participated on the Villasur expedition and was listed among those who died in the battle—but Nicolás did in fact survive the massacre, and eventually made his way back from present-day Nebraska to New Mexico. Archaeologist Dedie Snow of the state’s Historic Preservation Division champions the notion that Nicolás lived as a captive among the Pawnees for years, which made it possible for him to represent the Natives in such an anthropologically accurate way and to relate the narrative of the massacre as only a participant could. Pawnees who have studied the hides recognized some individuals carrying status objects.

Neg. No. 152691; Palace of the Governors artifact no. 11004/45.

(NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 152690; Palace of the Governors artifact no. 11005/45.

Nicolás would have been the master hide painter directing his Native apprentices in a traditional atelier, a method he would have known from his guild training. MacKenzie’s investigations have revealed both European and Native techniques, tool use, and concepts, strongly suggesting they are the work of a master and his apprentices from different cultural backgrounds. He believes Segesser II provides evidence of a more sophisticated integration of European and Native artists.

The use of borders on the hides is perhaps the most obvious example of this fusion. Borders are European in concept, and here they are formed of flowing acanthus leaves. Native hide paintings, winter counts being the most illustrative, do not have borders. Peering beneath the surface of the acanthus leaves reveals long brush strokes produced by a European paint brush. By contrast, the trees that appear in proliferation on the hides show a dabbing technique, the product of a Native brush made from a splayed plant stem.

Images painted on the hides were first drawn freehand or transferred by means of a pattern. Analysis shows evidence of pouncing, a technique employed to transfer images from a pattern to the surface of the prepared hide, which to date has been observed only in the border areas. In this method, an original image is traced by creating holes in a pattern. The outline of the image is transferred to the hide by tamping powdered graphite through the holes in the pattern. Pouncing has been a common technique for centuries.

There is evidence of freehand pencil drawing as well as pouncing, although the exact kind of pencil used remains unknown. The underdrawing on the Segesser hides was made with graphite, and the drawing instrument was a sharpened rectangle. Such a drawing would be produced by pencils from the period. Graphite deposits were also found in New Mexico in the Sandia Mountains east of Albuquerque adjacent to Tijeras Canyon and in the mountains east of Taos.

Pigments

One of the most dramatic scenes on the Segesser hides is the death of the commander of the ill-fated expedition, Pedro de Villasur. He appears lying on his back, attended by Jean L’Archevêque. Villasur is wearing the bright red coat of an officer. Cochineal typically provided the rich red color of military uniforms, such as those worn by the British Army. Because of time constraints, MacKenzie’s examinations did not include organic dye testing. So whether cochineal was used on the Segesser hides remains to be determined, as does the source for some of the other colors.

Father Juan Mínguez is clearly depicted running from Pawnee attackers with his blue habit pulled over his head and bearing a cross. The blue color of the habit Franciscans wore in New Mexico came from indigo, but Tom Chávez speculated that the blue in the Segesser hides was Prussian blue, the first synthetic color. When MacKenzie subjected the hide to multispectral analysis, however, he was surprised to find that the pigment was not Prussian blue and was indigo-based.

The questions, then, were how the blue in the Segesser hides lasted so long, and why it has a slight greenish cast. The solution MacKenzie hit upon for the blue pigment was Maya blue. As its name implies, Maya blue was used in Maya art, notably in decorating sculpture and ceramics. The bright blue pigment was also used in paintings in New Spain. It is remarkable for retaining its vibrancy for centuries.

After the Colonial period, the secret of producing Maya blue was lost—but recently the elusive formula has been recovered. Maya blue is a compound consisting of añil plants (Indigofera suffruticosa) and a natural clay called palygorskite. The archaeological literature establishes that palygorskite occurs in deposits in the Maya heartland. There are also large deposits in the far southwestern corner of the state of Georgia near the town of Attapulbus, which gives the clay its other name—attapulgite.

Lighter and darker shades of the same color appear on the hides. Tests showed that the varying shades came from the same source. The lighter shades were created by diluting the paint. One imagines the artist using a single pot of pigment and adding water or mordant to lighten the color.

The Hides

One of the abiding questions about the Segesser paintings was whether they were rendered on buffalo, elk, or some other kind of hide. To determine the type of hide, MacKenzie relied on a process called zooarchaeology by mass spectrometry (ZooMS). Inspired by an article he read, MacKenzie contacted York University in Great Britain and enlisted the assistance of their team of ZooMS researchers. ZooMs identifies a given species from the peptide mass fingerprint of collagen extracted from samples. The process of collecting samples involved extracting protein from the obverse surface of the Segesser hides by using electrostatic charge generated by gentle rubbing of a PVC eraser on the surface of the hide. The eraser crumbles were analyzed at York University, which maintains a growing database that makes it possible to identify specific species. The definitive answer was that the Segesser hides were buffalo.

Knowing that the hides are buffalo leads to a lot of additional information and likely conjecture, because the processes involved in preparing buffalo hides are well known. Each Segesser hide painting consists of multiple buffalo hides stitched together. A typical buffalo hide would have come from either a cow or bull weighing a thousand pounds. After being removed from the carcass, processing the hide began with soaking. This was followed by fleshing, which removed all remnants of flesh from the hide.

In the case of the hides destined for use as a canvas for painting, both the hair side and flesh side were scraped clean. Thinning, which was required for softening, left only a thin layer of tightly bound collagen fibers. Typically, a hide was next brained, a process whereby brain matter, often mixed with grease, was worked into the hide. MacKenzie was unable to determine whether the Segesser hides were brained because he did not have the opportunity to perform that type of analysis, but there is a yet-to-be identified yellowish coating underneath the pigment on the hides that may be evidence of braining.

Pulling is a step that involves working the hide back and forth around an upright pole, further softening the hide. A final step in preparing a hide is smoking. Smoking could be accomplished intentionally or simply by close exposure to campfires. It is unclear whether the Segesser hides were intentionally smoked, but there is clear evidence of exposure to smoke in the form of a dark, greasy substance in some parts of the hides. Perhaps this substance was deposited when the painted hides hung in a building in proximity to a fireplace. Interestingly, the Segesser hides show three distinctly different nail holes, which suggests that they only hung in three places and at three different time periods.

Conclusions

Looking back with the perspective of thirty-four years since the Segesser hides arrived in Santa Fe, Tom Chávez notes, “The Segesser hides are important documents of New Mexico history, and they are unique works of art. They are just as significant to New Mexico today as when they were acquired, perhaps even more so, since so much has been learned about them in the intervening years.”

There are questions that the application of cutting-edge science has still not answered, but the amount of new information Mark MacKenzie uncovered in his decade-long investigation will doubtless lead to even more discoveries. He left a complete archive of all the data he amassed over the years; all those gigapixels and terabytes await a similarly inquisitive researcher to further his valuable work of science in the service of history so that the Segesser hides can continue to inform us as they reveal their secrets far into the future.

Sources

Thomas E. Chávez, “The Segesser Hide Paintings: History, Discovery, Art,”

Great Plains Quarterly 10, no. 2 (1990): 96-109.

Gottfried Hotz, The Segesser Hide Paintings: Masterpieces Depicting

Spanish Colonial New Mexico. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press,

1991.

Interview with Mark MacKenzie, August 22, 2019.

—

Dr. Rick Hendricks is the New Mexico state records administrator and a former state historian.