Embroidering the Canon

The artists of the 1960s and 1970s who reimagined photography

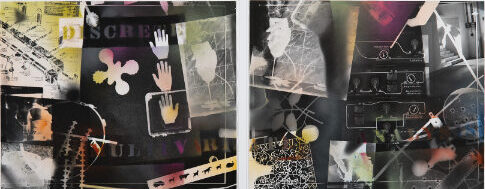

Thomas J. Barrow, Discrete Multivariate Analysis, 1981.

Gelatin silver print photograms with automotive lacquers and

epoxy enamel. 16 × 19 ¾ in. Collection of the New Mexico

Museum of Art. Gift of Frank and Patti Kolodny, 1990

(1990.1.1ab). © Thomas Barrow. Photograph by Cameron Gay.

Thomas J. Barrow, Discrete Multivariate Analysis, 1981.

Gelatin silver print photograms with automotive lacquers and

epoxy enamel. 16 × 19 ¾ in. Collection of the New Mexico

Museum of Art. Gift of Frank and Patti Kolodny, 1990

(1990.1.1ab). © Thomas Barrow. Photograph by Cameron Gay.

By Emily Withnall

When an eclectic scattering of artists across the United States began pushing the boundaries of what photography could be in the 1960s and ’70s, they did not collectively name themselves. Organizing their movement would have been the antithesis of what they were trying to do. Though it is impossible to fully capture the range of approaches each artist took in creating their work, they were each trying to challenge the idea that photography was a window into reality. To these iconoclastic artists, photography was full of possibility, but it was not static or sacred.

The New Mexico Museum of Art exhibition Transgressions and Amplifications: Mixed-media Photography of the 1960s and 1970s (on view through January 8, 2023) features many of the artists who pushed to expand the boundaries of what photography could be. To provide historical context, Museum of Art Curator of Photography Katherine Ware includes a comparison of a 1931 photograph by Edward Weston with a 1972 piece by Betty Hahn to help viewers better understand the rules later artists sought to break.

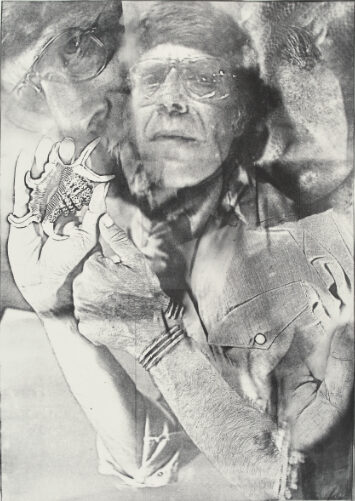

In a portrait of his great-grandfather by Van Deren Coke, a brightly lit outline of a bust can be seen against a black background. The figure’s hair is wavy and the bust is fractured, like an image of clay with pieces coming off in chunks, leaving dark holes behind. The black background also appears to be crumbling and is set against a larger sepia-toned background. Light seeps from the seams where black and sepia collide.

“He photographed this tiny ambrotype of his great-grandfather then printed it as a photogravure,” says Ware. “He is making a new work of art about an old photograph, referring back to that history but commenting on it.”

Where an ambrotype is a positive photograph on glass, a photogravure is not usually considered to be photography, because the film negative is not developed in a darkroom. Instead, the negative is transferred directly onto a copper plate, where the image is engraved with ink. By combining these techniques and subverting the idea of what a portrait can be, Van Deren Coke was, like many of the other photographers in the exhibition, interested in stretching the definition of what counted as photography and how it operates.

Some artists created photography without a camera, and instead used early versions of Xerox machines, or manipulated found photos, among other techniques. Ware says for most of the featured artists, proving that photography could be severed from cameras wasn’t a specific aim. However, one artist, Thomas Barrow, who graduated from the Institute of Design in Chicago, was very interested in this question.

In Barrow’s Discrete Multivariate Analysis, a gelatin silver print photogram (a photograph made without a camera), a diptych overwhelms the viewer with numerous images that appear like film negatives of various items like screws, the repeated outline of a pedestrian “stop” hand signal, mechanical instructions, a shower head, and a shadow of a person illuminated along a staircase, alongside numerous other inscrutable images.

“Barrow was particularly sophisticated in playing with photo history and the question of, ‘How far can I push this?’” says Ware. “There’s another piece by him in the show that refers to nineteenth-century stereographs and he dares to tint the print pink, just to see if he can get away with it.”

Many of the artists in the exhibition viewed a photo as an object unto itself. The physical photo was as integral to their art as the subjects or meanings framed within the photo. Artists marked, pierced, tore, crumpled, or otherwise used and challenged the fine art world’s notion of the photograph as inherently truthful or sacred.

“The transgression is that the fine-art print was considered this pristine thing everyone has to wear gloves to handle,” says Ware. “But these artists added old photo processes, used ink, wrote and sewed on their prints. Most of them are unique objects rather than something that can be reproduced from a negative.”

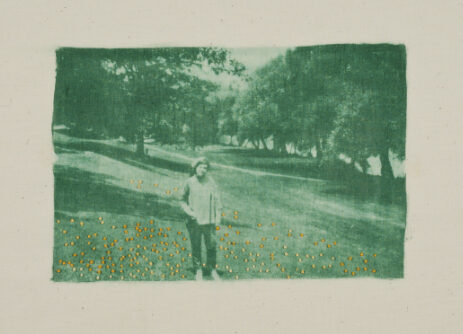

Photographer Betty Hahn painted on her photos, applied Xeroxed images to fabric, and embroidered photographs. In her photo printed onto fabric, Barbara, Gennesse Park, a woman stands in a knoll of trees. The woman, grass, trees, and sky are all various shades of green. Raised knots of thread add color and texture to the photograph, appearing like small flowers in the field.

Hahn and other women artists stretching the limits of photography worked to incorporate craft and skills that were often considered to be “women’s work” into their art. Ware says the women photographers working in these varied mediums in the 1960s weren’t always a part of the women’s movement because they were often too busy teaching, making art, and running households. Nevertheless, in addition to raising children and caring for their homes, they made art that addressed the female experience and the changing roles of women in society, as well as questioning the ways photography, in particular, was understood.

One photographic predecessor to these iconoclasts was Alfred Stieglitz. His photo series of clouds and of Georgia O’Keeffe asked viewers to engage with the photographs emotionally and to see the multifaceted nature of any subject rather than one fixed image. But where photographers like Adams and Stieglitz were concerned with precision and camera technique, the artists of the 1960s and 1970s wanted to go further.

“This generation comes along and asks, ‘Why can’t it be in color? And why is it just pictures of one thing? And how do you express what it’s like to be a parent or in love in a single frame?’” says Ware.

At the time these artists were working, photography was still relegated to the edges of the fine art world. Where art broadly acts to break norms and push boundaries, Ware says a tension exists between art as transgressive and fine art as a categorization that maintains the status quo. The iconoclasts of the ’60s and ’70s wanted to challenge the gatekeeping that was occurring in the fine art world, and especially where photography was concerned.

“They all saw The Family of Man at the MoMA and admired the work, but they wanted to do something different,” says Ware, referencing the 1955 exhibition of global solidarity following World War II that featured hundreds of photographers.

In the Museum of Art exhibition, viewers can compare Edward Weston’s realistic gelatin silver print of a cabbage leaf with Betty Hahn’s image, Lettuce. Hahn’s photo is a green-tinted gum bichromate print on fabric. Lines in the lettuce leaf are embroidered in black and white. Unlike Weston’s photo, Hahn has blurred the detail of the leaf and instead calls the viewer’s attention to the thread.

Hahn was among a small group of photographers who came to New Mexico to teach and continue their work in the 1970s. When Van Deren Coke arrived at the University of New Mexico to found the art museum there in 1962, fellow iconoclasts Betty Hahn and Tom Barrow soon followed. Though some enclaves existed in Albuquerque (as well as in Rochester, New York; Bloomington, Indiana; and Gainesville, Florida), Ware says the artists were not a cohesive group overall.

The women artists of that time were often overlooked or further marginalized within their own boundary-breaking non-movement.

“Bea Nettles studied with some traditional teachers who felt that her subject matter about women and families was not appropriate for art,” says Ware. “And they literally locked her out of the darkroom, so she found other techniques and methods for producing her work.”

Joyce Neimanas, married to fellow iconoclast artist Robert Heineken, is known for her early work in digital imaging, but prior to that she pushed the boundaries in a variety of ways including using stills from adult videos. Several of her works in the show explore women’s sexuality.

“She incorporated texts from the Kinsey report in some of her pictures,” says Ware. “She was very interested in media and found photography and so she was doing screen grabs of anonymous bodies, then handwriting words from the report and giving the pictures very clinical titles.”

Likewise, Joan Lyons, who was married to photographer, curator, and teacher Nathan Lyons, benefited from a shared creative milieu, though her work was somewhat overshadowed. She worked extensively with early Xerox machines to create personal photographs based on her experiences. For Lyons, Hahn, Nettles, Neimanas, and other women artists, being overlooked or relegated to small women’s shows was commonplace, though they were always glad for opportunities to share their work.

Ware points to the ’60s and ’70s as being a period of flux and huge cultural shifts in the United States, and much of those shifts infused the transgressive photography these artists were making, whether they were actively a part of social movements or not. “There’s some commentary in the work that is arguably oblique to viewers now,” says Ware. “But the adventurous spirit and sense of a disordered world comes through clearly in many of the pieces.”

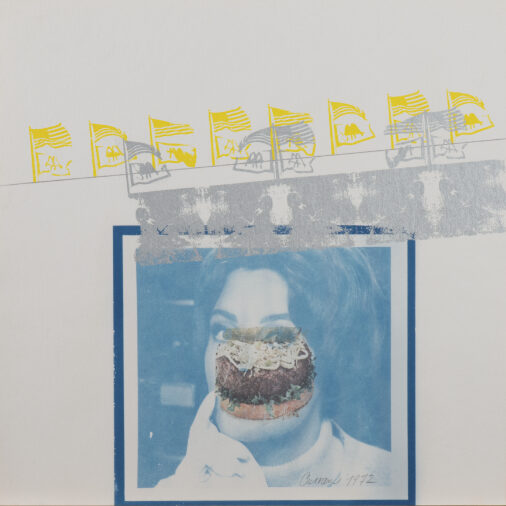

In one such photo, Darryl Curran’s Nutrition Temple Series #14, a magazine-appropriated portrait of a woman is overlaid with an image of a hamburger that obliterates most of her face except for her eyes, forehead, and shiny coiffed hair. Two different screen prints with repeating patterns are stamped above the photo—one of gray cow noses sprouting flag poles with McDonalds and American flags, and another yellow print above it with additional McDonalds and American flags.

Because the majority of the artists in the exhibition created multi-media work, viewers might be inclined to wonder why they chose photography as a medium. Ware says it’s a question each artist would likely answer differently.

“I think they weren’t that interested in the question,” says Ware. “Their work doesn’t fit in a conceptual box, and they liked that.”

The etymology of “photography” is “to write with light”—a definition many of the artists of the 1960s and ’70s broke from. And while many often did not use a camera or light to create their work, others worked with older photographic methods to capture the light. One such method was the cyanotype, which allowed artists to create a negative on paper painted with photosensitive blue solution. In the 1800s, architects used cyanotypes to produce blueprints, but iconoclast Brian D. Taylor wanted to play with that historical lens in his own work.

In Taylor’s Labyrinth No. 5, a cyanotype reveals a zoomed-in view of walls, floors, and their seams. It is impossible to see the whole structure so viewers are left with simply the impression of geometric shapes. In an image with no clear focus, light pours from the lines where the walls and floor meet, suggesting that perhaps light is the subject.

“He’s using the architecture and the fact that the cyanotype wipes out details to make this very abstract composition,” says Ware. Of the group of artists as a whole, she adds: “They’re all over the place. That’s part of why they can’t be considered to be a defined movement.”

Although the exhibition primarily features artists from the 1960s and ’70s, Ware says she has included work by Lorna Simpson, whose work provides a more contemporary example of multimedia photography. In her diptych Back 1991, a portrait of the back of a Black woman’s head is paired with an actual black braid set in a square inside the wooden frame. Words in the center of the frame read: “eyes in the back of your head.”

“The question that really fascinates me is always—why did she need to add the braid, or why did he need to add the paint, or why did she need to add the handkerchief?” says Ware. “The photographs are crucial, but they’re reaching for something that they can’t say without the added elements. How do you reflect the experience of a feeling or a mental state?”

Making meaning of the photographs can sometimes be challenging. The artists were often less interested in portraying a subject and more interested in communicating varied emotions, perceptions, and realities. The images in the show are paired with descriptive and contextual labels, but many viewers may find themselves probing for meaning or asking where boundaries should be drawn when defining an artistic medium.

For Ware herself, this isn’t always an easy answer. Although she acknowledges the sophisticated tools digital cameras offer to the heirs of the iconoclasts in the exhibition, Ware points out that digital cameras use numbers to capture images—not light. In the context of an exhibition about transgressions, however, the question of whether digital photography counts as photography is overshadowed by a bigger question: What isn’t a photograph?

“The message of the show is the fluidity of definitions and the requirements of expression,” says Ware. “People reach for the tools they need to say what they’re trying to say.”

—

Emily Withnall lives and writes in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Her work can be read at emilywithnall.com.